|

| Anna Harbine, Tom McArthur, Logan Camporeale and Katie Enders tweeting the Great Fire of 1889 at the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture |

Here is a fun project that came together quickly, and is going live even as I type: Spokane historians to re-enact the city’s great 1889 fire, on Twitter.

On August 4th, 1889, the frontier city of Spokane pretty much burned to the ground. The fire could not have been more dramatic. The blaze started at 6 p.m. and Spokanites were confident that their new, state-of-the-art fire fighting equipment would take care of it. But the city official in charge of the water works was off fishing, and a mechanical failure deprived the firefighters of water. The inferno raged into the night, as a firestorm devoured the entire downtown in about three hours. The scene was chaotic--a burning man leapt from the second story of a hotel, while the mayor rode through the crowd on horseback looking for someone who could fix the water system. The next day Spokane was a pile of smoking ruins.

|

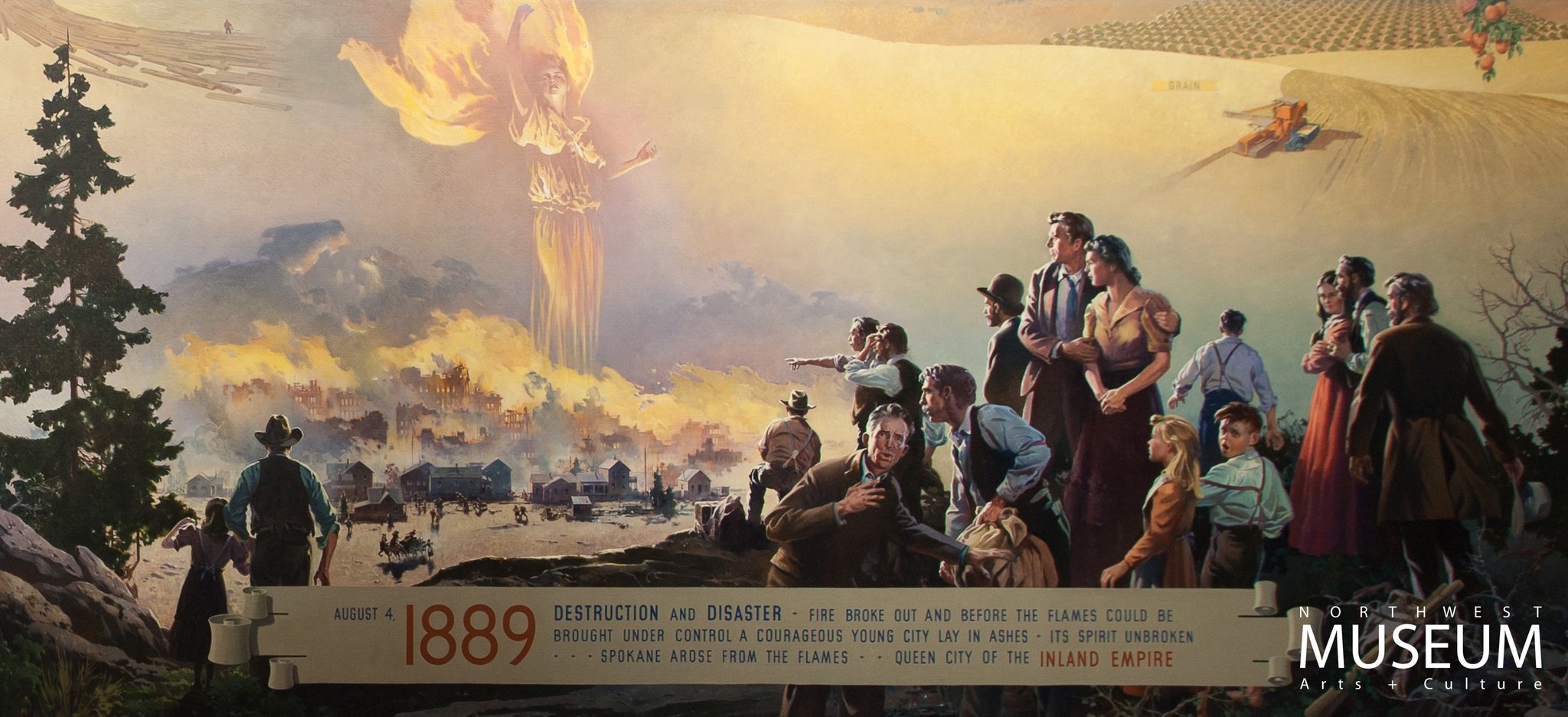

| Dramatized view of the Spokane Fire from a 1930s bank mural, now at the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture |

I shared the idea with some local historians and institutions, including two employees of the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture, Anna Harbine and Logan Camporeale. They loved the idea, and quickly obtained permission for the museum to spearhead the effort and to use their Twitter feed.

So yesterday we met at the museum for about two hours and hammered out the tweets. Harbine, the museum archivist, had a long table ready with writings and photographs about the fire. Harbine and Comporeale were there, along with Katie Enders from the Spokane Historic Preservation Office, Tom McArthur, two people from the museum's marketing and social media, and Spokesman reporter John Webster. We agreed on a hashtag of #greatfire1889. We talked a little bit about some of the issues and agreed to tweet in the present tense, to do things in real time as much as possible, and to tweet about the fire from August 6 to a somewhat arbitrary end point of August 14th. We created a shared Google Doc and started punching out the tweets.

It was a blast. We each worked from a different resource about the fire, books and letters and newspaper articles, and pulled out striking and dramatic bits. The 144-character limit of Twitter was not as much of a problem as I would have thought, and we quickly figured out that 144 characters equaled about one-and-a-half lines on the Google Doc. We tried to keep the Tweets roughly chronological as we added them to the document. The Google Doc had the great advantage of allowing everyone to see what the others were working on and avoiding duplicate tweets on the same subject. We added brief citation notes to each tweet, not to be tweeted but to document where we had found the information in case there were questions later. We also looked at some of the dramatic photographs that Harbine had identified from the collections and wrote tweets to highlight those images.

After ninety minutes or so we had in excess of thirty tweets that did a really nice job of telling the story of the fire. Camporeale then assigned times to each tweet. The tweets went into Hootsuite, a social media tool that allows one to schedule tweets in advance, each set to be tweeted at the right time.

Honestly I went into the meeting yesterday thinking that we would agree that it was too late to launch such a project for the next day and we should do it next year. But the enthusiasm of the MAC employees swept us all along.

Live tweeting a historical event would make a great classroom project for digital and public history courses. This presentation lays out how they did a similar project on the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald has some good tips. Here are the steps as I see it:

- Pick a historical event. Something dramatic, well-documented, and with contemporary interest. It needs to be an event that took place over a few days, not months. Choose a time period that you will be tweeting, maybe 3-7 days?

- Choose a hashtag. Make sure that it has not been taken.

- Assemble some resources. It really worked well to have different people pulling their tweets out of different sources. Resources could be a mix of physical and digital, with digitized books and newspapers offering a rich set of perspectives. Make a Google Doc with links to the digital resources.

- Write the tweets. If I were working with a larger class, I would organize the Google Doc a bit in advance by making headings for each days tweets. Encourage students to find relevant images to attach to the tweets.

- Schedule the tweets with Hootsuite or a similar social media manager.

Publicity is also a concern. Which Twitter account will be used? Who will retweet the tweets? Can you get local media interested? In the #greatfire1889 project we lucked out that the local newspaper took and immediate interest. In fact, our project was on the top of the front page today:

No comments:

Post a Comment