I want to write about a book about how cities use their own history to define themselves and to present themselves to visitors and the world at large. My project is partly inspired by Clint Smith's wonderful book How the Word is Passed. Those of you who have read the book (and if you haven't go do so right now), know it is an analysis and travelogue of some of the historic sites of American slavery. Smith visits sites like Monticello, Goree Island, Whitney Plantation, and Angola Prison. The structure is deceptively simple--each chapter is devoted to one site. Smith explains the history of the site using the latest scholarship, he visits the site and writes about that experience, and then he talks with either visitors to the site or the folks who run it. Each chapter is interesting in its own right, and together they are an engaging survey of the current state of the public history of slavery in the United States.

I had just read the book when I visited Salt Lake City last spring for the National Council on Public History conference. The capitol of Utah and the Mormon Church is a place that takes its history

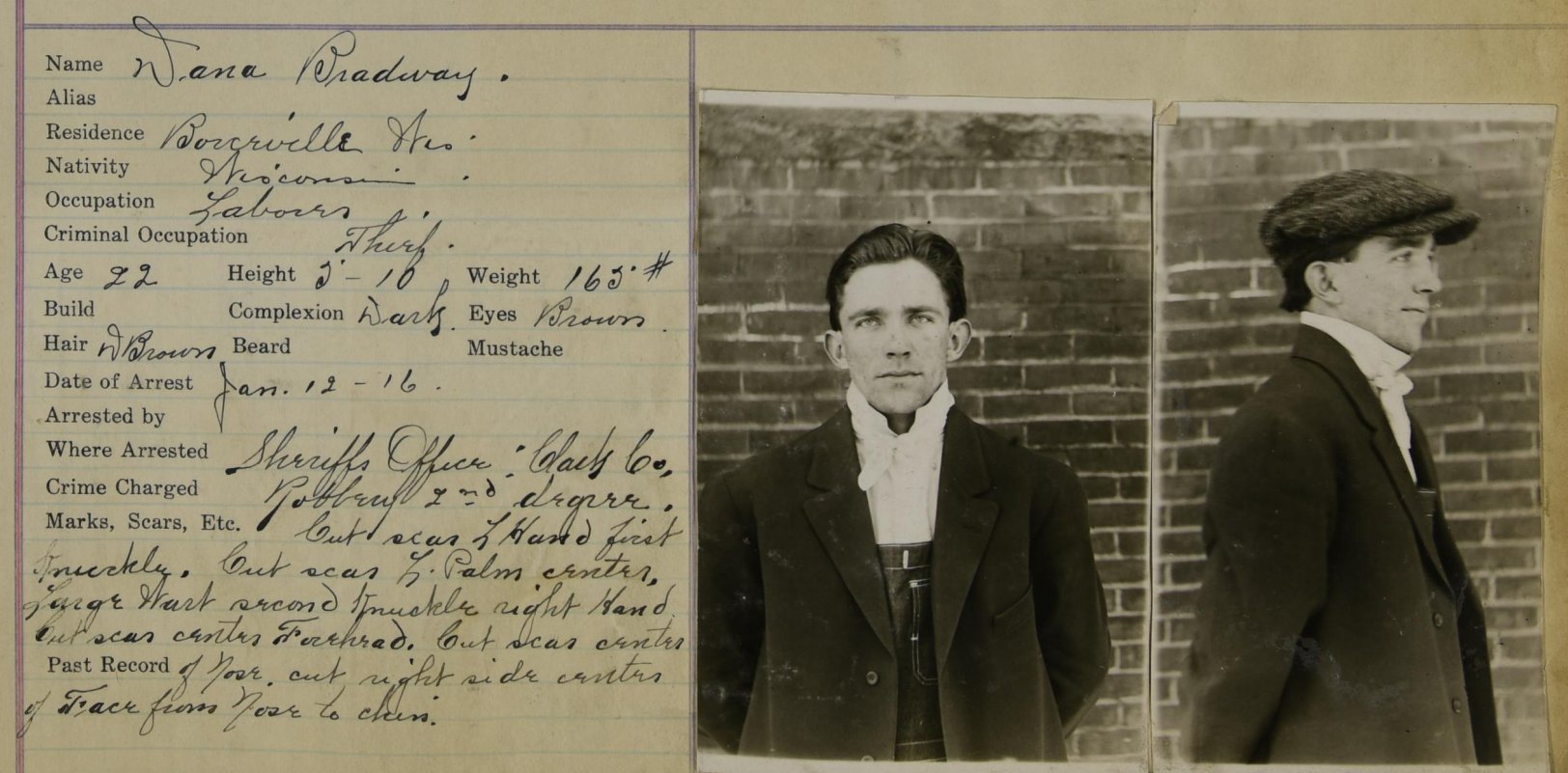

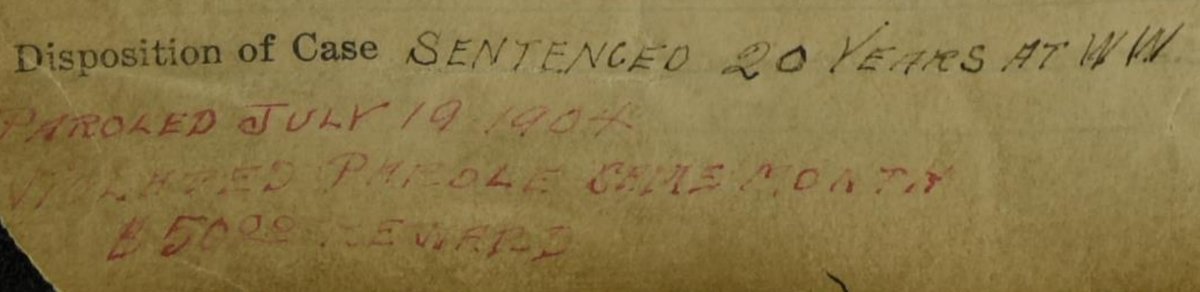

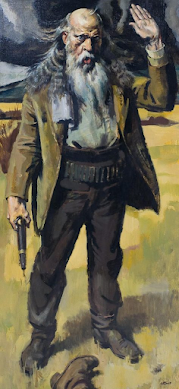

seriously, with multiple museums and monuments celebrating the history of Mormonism. There is also a counternarrative going on, At a conference reception at the Alta Club, a terrifying portrait of Porter Rockwell greets visitors as they come through the entrance. Rockwell was a colorful figure, often called "Brigham Young's assassin." His crazy eyes stare through the door and at the statue of Brigham Young across the street. The Alta Club was founded largely by the non-Mormon business elite of Salt Lake, and the location of the portrait is a clear dig at the traditional Mormon history of the region.

|

| Porter Rockwell might shoot you. |

I should write about this, I thought.

So here is the idea: A book about how cities use their history. Each chapter is a different city. Each begins with a history of the community, then transitions to a journalistic visit to the place, describing and analyzing the main narrative (or narratives), current controversies, and some conversations with public historians and advocates. As I describe this, it is such an obvious idea that I feel like the book must exist already--but I don't think it does.

So what cities do I analyze? I want to stick to North America, I am a historian of the United States and would be quickly out of my depth tackling London or Kyoto. They have to be cities that think of themselves historically, that present their histories front and center. This rules out most American cities, where history is an afterthought or at best a niche interest. I love the history of my town, Spokane, but no one comes here to explore that history nor is history front and center of how we think of ourselves. And I want some variety in the 8-10 communities.

Here are the cities are I am thinking of so far:

So what cities do I analyze? I want to stick to North America, I am a historian of the United States and would be quickly out of my depth tackling London or Kyoto. They have to be cities that think of themselves historically, that present their histories front and center. This rules out most American cities, where history is an afterthought or at best a niche interest. I love the history of my town, Spokane, but no one comes here to explore that history nor is history front and center of how we think of ourselves. And I want some variety in the 8-10 communities.

Here are the cities are I am thinking of so far:

.

Salt Lake City, for the reasons above. I have abundant notes on my visits to the museums, historical societies and the state capitol, and I have been doing some background reading and taking notes. I also want to write about a counter-narrative to the LDS history that dominates the landscape, the stories told by the gentiles of Salt Lake City.

Santa Fe is an obvious choice. This one will be fun. The old Spanish colonial town has a fascinating and often raw history. But its presentation of itself as quaint and colonial is an early 20th-century marketing ploy, with "American" style buildings torn down or refaced with faux-colonial adobe. And there are some fun local controversies, like the recent toppling of a statue of a frontier army soldier and other statue controversies.

Charleston and/or New Orleans as a southern city. Maybe both? Charleston is both the site of Revolutionary War battles and Confederate shrines. There is an ongoing struggle over the city's public history, between Black public historians and old-guard white public historians, beautifully chronicled in Denmark Vesey's Garden. New Orleans of course has an even richer history and history of public history and tourism. I worry about the overlap of doing both--slavery and the Civil War--but there are so many differences perhaps I can write about both.

Palm Springs offers a different history and public history. A desert resort for Hollywood stars trying to get away from the paparazzi, it is known for its rich collection of midcentury architecture. As I write this I am on my way there for Modernism Week. This will be a fun contrast to the other locations.

Boston has worked hard to claim the legacy of the American Revolution all for itself, ever since Paul Revere got off his horse. There is Seth Bruggerman's Lost on the Freedom Trail.

Philadelphia has been saying "Oh no you don't the Revolution is ours!" to Boston for the same amount of time. Great preservation stories in Philly. Like Charleston and New Orleans, I worry about too much overlap.

Washington D.C. might be the final chapter, a city where the public history is at war with itself. We have the staid Smithsonian museums, the African American and American Indian museums, various commercial failures like the late Spy Museum, and of course the January 6th insurrection with its faux-constitutional veneer, which could be a chilling closing to the book.

Reader, what other cities should I consider? I am going to Montreal next month for the National Council on Public History conference and will take a close look. San Francisco is a strong candidate, not just Gold Rush history but the intentional development of Chinatown as a tourist attraction.

Where else?

Reader, what other cities should I consider? I am going to Montreal next month for the National Council on Public History conference and will take a close look. San Francisco is a strong candidate, not just Gold Rush history but the intentional development of Chinatown as a tourist attraction.

Where else?